Florida classroom guidelines for its new African American History Strand, as adopted by the State Board of Education, state that classroom instruction should include “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

William Allen, who is a professor emeritus of political science at Michigan State University, defended that strand this way: “I see what Frederick Douglass meant when he described his slave mistress teaching him to read only at the beginning because his owner put a stop to it. But that small glimmer of light was enough to inspire him to turn it into a burning flame of illumination from which he benefitted and his country benefitted.”

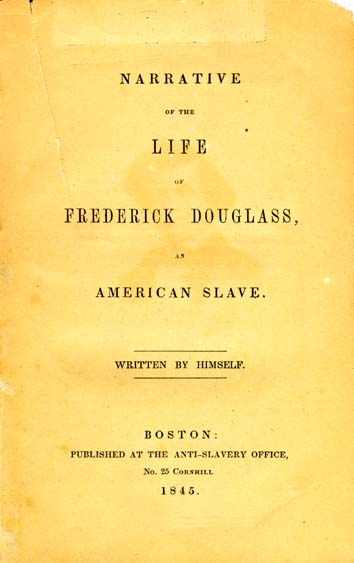

I’ve read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (1845). It is a horrifying book, and I hope more people read it.

The book contradicts the claim that Douglass developed reading because of slavery. He learned to read in spite of slavery. If he had been free, learning to read would have been legal. Slavery specifically sought to withhold that personal benefit from him.

He recounted in Chapter VII that as a child in Baltimore, one of his mistresses, Mrs. Auld, was new to slave-owning, and “very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters.” Then her husband found out “and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read” and to do so “would forever unfit him [Douglass] to be a slave.”

That rebuke turned Mrs. Auld into a cruel mistress who did everything she could to keep him from learning more. “I was most narrowly watched.”

Out in the street, though, he learned at a shipyard that L, S, F, and A stood for larboard, starboard, fore, and aft.

“I immediately commenced copying them, and in a short time was able to make the four letters named. After that, when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could write as well as he. The next word would be, ‘I don’t believe you. Let me see you try it.’ I would then make the letters which I had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask him to beat that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which it is quite possible I should never have gotten in any other way.”

At home, when no one was around, he practiced with the family’s young son’s discarded Webster’s Spelling Books. “Thus, after a long, tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.”

But he had learned to hate slavery long before he learned to read and write.

Warning: What follows is sadistic brutality. In Chapter I, he recounted how, as a very young boy, he saw his aunt whipped by their master.

“Before he commenced whipping Aunt Hester, he took her into the kitchen, and stripped her from neck to waist, leaving her neck, shoulders, and back, entirely naked. He then told her to cross her hands, calling her at the same time a d——d b—h. After crossing her hands, he tied them with a strong rope, and led her to a stool under a large hook in the joist, put in for the purpose. He made her get upon the stool, and tied her hands to the hook. She now stood fair for his infernal purpose. Her arms were stretched up at their full length, so that she stood upon the ends of her toes. He then said to her, “Now, you d——d b—h, I’ll learn you how to disobey my orders!” and after rolling up his sleeves, he commenced to lay on the heavy cowskin, and soon the warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor. I was so terrified and horror-stricken at the sight, that I hid myself in a closet, and dared not venture out till long after the bloody transaction was over.”

In Chapter VIII, Douglass’s family was being split up as property after his master died. The master’s son was a possible heir, and “to give me a sample of his bloody disposition, took my little brother by the throat, threw him on the ground, and with the heel of his boot stamped upon his head till the blood gushed from his nose and ears.”

The book has eleven chapters — and many more incidents of savagery. Douglass concludes with the hope “that this little book may do something toward throwing light on the American slave system, and hastening the glad day of deliverance to the millions of my brethren in bonds.”

Nothing in the book tells how slavery personally benefitted the enslaved — or the masters. Douglass said it made them cruel and rage-filled: “Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness.” Slavery benefitted no one.