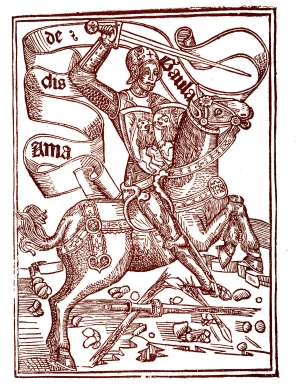

Twenty years ago, I began translating a medieval Spanish novel of chivalry, Amadis of Gaul. It falls within the Arthurian tradition, telling the story of the greatest knight in the world, Amadis, who lived in an era before King Arthur. (The once-upon-a-time setting doesn’t bear scrutiny; the Kingdom of Gaul is also imaginary.)

The earliest existing copy of the novel dates to 1508, but the story had originated two centuries earlier, a truly medieval tale of sword and sorcery. Once the printing press was invented, the novel became one of Renaissance Europe’s first best-sellers.

Here is an excerpt from Chapter IX. At this point, the teenage Amadis has recently become a knight and is achieving prodigious feats. He had been discovered as an infant in a box floating in the sea, so he is known as the Childe of the Sea, but we learned in Chapter 1 that he is actually the son of King Perion and Queen Elisena of Gaul — but no one knows that, including his parents (it’s complicated; medieval stories are notoriously complicated). He was adopted and raised by a nobleman in Scotland, and is now accompanied by Agrajes, a Scottish prince.

Meanwhile, King Abies of Ireland has invaded Gaul, and the Childe of the Sea comes to the aid of King Perion. After a hard-fought battle, the Childe of the Sea has been chosen to fight King Abies hand-to-hand for the kingdom.

I translated it as close to the original medieval Spanish as I could. It was meant to be read aloud, so you will notice references to the audience. You may also notice the distinctive medieval notions of honor, such as the Queen personally attending to the Childe of the Sea, and the townspeople singing to their victor.

+

Once the battle between King Abies and the Childe of the Sea was arranged, as ye have heard, those on both sides saw that most of the day had already passed, so they agreed to wait until the next day, against the wishes of the two combatants. They could clean their weapons as well as treat their wounds, and because all the men on both sides were injured and tired and they wished to rest and recover, each side went back to where they lodged.

The Childe of the Sea, riding bare-headed, entered the town with King Perion and Agrajes, and everyone in the town sang to him:

“Oh, good knight, God help thee and give thee virtue

that thou mayst end well what thou hast begun to do!

Oh, handsome knight! In him, chivalry gets its due

for he above all keeps it most noble and true!”

When they arrived at the palace of the King, a damsel came and said to the Childe of the Sea:

“My lord, the Queen asks you not to remove your armor until ye arrive at your rooms, where she waits for you.”

This was agreed to by the King, who said:

“My friend, go to the Queen, and Agrajes may go with you to keep you company.”

Then the King went to his rooms, and the Childe and Agrajes to his, where they found the Queen and many ladies and damsels, who took their armor. But the Queen would not allow anyone to touch the Childe besides her, and she removed his armor and covered him with a cloak. At this time the King came and saw that the Childe was injured, and he said:

“Why did ye not ask for a delay on the day of the battle?”

“That was not necessary,” said the Childe. “There is no wound that would keep me from it.”

Then they treated his wounds and they gave them supper.

The next morning the Queen came with all her ladies and found the knights talking with the King. Mass began, and after it was said, the Childe of the Sea armed himself not with the arms from the previous day, because nothing remained that was useful, but with others that were more handsome and strong. He bid goodbye to the Queen and the ladies and damsels, and he rode off on a well-rested horse that they had for him at the gate of the castle.

King Perion carried his helmet, Agrajes his shield, and old knight named Agonon, who was well-esteemed at arms, his lance. Because of Agonon’s great nobility in the past, and for his courage as well as his virtue, he was the Childe’s third, after the King and the son of a King. The shield that Agrajes carried had a field of gold with two blue lions on it, facing each other as if they wished to bite each other.

When they left the gate of the town, they saw King Abies on a large black horse, fully armed, though he had not yet strapped on his helmet. The villagers and the enemy soldiers arranged themselves to watch the battle as well as they could. The field had been marked and a stockade erected with many stands around it.

They strapped on their helmets and picked up their shields. King Abies put a shield around his neck with an indigo field that displayed a giant and a knight next to it who was cutting off its head. He used that insignia because he had fought against a giant that had entered his lands and left barren all that it encountered, and because he had cut off its head, he carried that feat’s representation on his shield.

After both took up their arms, all others left the field, and each side commended its knight to God.

Without delay, they had their horses charge at a gallop. Since both were strong and wholehearted, at the first strike all their arms failed. Their lances broke, and both the men and the horses struck each other so hard that both were knocked off. Everyone believed they were dead. Pieces of the lance were embedded in their shields and the iron tips had reached their flesh.

But as both were agile and brave of heart, they quickly got up, removed the pieces of lance from themselves, and took their swords in hand. They attacked so fiercely that those who were around the field were frightened to see it.

Yet the battle seemed unequal, not because the Childe of the Sea was not well built and reasonably tall, but because King Abies was a palm taller than any other knight, and his arms and legs seemed to belong to a giant. He was well loved by his people and always demonstrated good conduct, except that he was more arrogant than he ought to have been.

The battle between them was both cruel and relentless, with no time to rest, and the blows were so great that they seemed more like twenty knights. They cut at each others’ shields, which fell to the field in large pieces. They dented each others’ helmets and rent each other’s hauberks. Thus each made his strength and his passion known to the other. And the great strength and quality of their swords made their armor almost worthless, so that frequently they cut flesh, since nothing remained of their shields to protect themselves.

So much blood flowed that it was amazing they remained standing, but so great was the passion that each carried within him that they hardly felt it. And so they continued in this first battle until the third hour of the day. Neither weakness nor cowardice could be detected in either. Instead they fought with spirit, but the sun heated their armor and made them fatigued.

At this time King Abies stepped back and said:

“Wait and let us straighten our helmets, and if thou wishest, let us rest a bit. Our battle will not be delayed much. And although I would do thee mortal harm, I esteem thee more than any other knight against whom I have fought, though thou shouldst not take my esteem as a wish not to do thee ill, for thou killedst him whom I loved dearly and thou givest me great shame that this battle has lasted so long in front of so many good men.”

The Childe of the Sea said:

“King Abies, this gives thee shame, but not having come arrogantly to do so much wrong to he who does not deserve it from thee? Thou shouldst see that men, especially kings, ought not do what they can but what they must, because often it happens that the harm and violence that they wish on those who do not deserve it in the end befalls on themselves, and they lose all, even their lives. Now, if thou wishest me to let thee rest, there are others, greatly oppressed, who wish respite from thee, which thou wilt not grant, and because thou feelst what thou hast made them suffer, prepare thyself, for thou shalt not rest with my permission.”

The King took up his sword and what little remained of his shield and said:

“This passion ill behooves thee, for it puts thee into a danger from which thou shalt not leave without losing thy head.”

“Now use thy might,” said the Childe of the Sea, “for thou shalt not rest until thy death comes to thee or thy honor is finished.”

And they attacked with more wrath than before, and so bravely that it seemed that the battle had begun at that moment and they had not struck a blow earlier that day. King Abies, who was very skilled in the use of arms, fought wisely, protecting himself from blows and attacking where he could do the most harm. The Childe moved and attacked with amazing speed and struck so hard that everything the King knew seemed wrong. In spite of himself, things were going badly, and he began losing ground.

The Childe of the Sea had just destroyed the shield on his arm, and nothing remained of it, and had cut to the flesh in many places. The King’s blood flowed freely. He could no longer attack, and his sword twisted in his hand. He was so afflicted that he almost turned his back to the Childe as he searched for a place of refuge in fear of his sword, which he felt so cruelly in his flesh.

But when the King saw that he had no choice but death, he turned, took his sword in both hands, and ran at the Childe, meaning to strike the top of his helmet. The Childe lifted up his shield, which took the blow, and the blade sunk so deep that it could not be withdrawn. As the King pulled back, he exposed his left leg, and the Childe of the Sea struck such that his leg was cut in half.

The King fell onto the field. The Childe came at him, pulled off his helmet and said:

“Thou art dead, King Abies, if thou dost not surrender.”

He said:

“Truly I am dead, but not vanquished. Instead I believe that my arrogance killed me. I beg thee to pledge that my war party will suffer no harm and may take me to my homeland. I forgive thee and those whom I wished to harm, and I order returned to King Perion all that I took from him. I beg thee to let me make confession, for I am dead.”

The Childe of the Sea, when he heard this, felt great and amazing sorrow for him, but he knew well that the King would not have sorrow for him if he had won.

Once all this had happened, as ye have heard, the invaders and the townspeople came together, since the safety of all was assured. King Abies ordered that everything he had taken from King Perion be returned, and King Perion pledged to him that all his troops would be secure until they had taken him to his lands. Then, having received all the sacraments of the Holy Church, King Abies’s soul left him. His vassals, with great lamentations, took his body back to his lands.

King Perion and Agrajes and other outstanding men of his court took the Childe of the Sea from the battlefield with the kind of glory that the victors of such deeds usually earn, not only for the honor but for the restoration of a kingdom to someone who has lost it. The Childe of the Sea went to the King and Agrajes, who were waiting for him, and they entered the village. Everyone sang:

“Come, good knight, and welcome!

Through you we have regained

our honor and our joy!”

And so they went to the palace, where in the Childe of the Sea’s rooms they found the Queen waiting with all her ladies and damsels, in great merriment. The women raised their arms to take him from his horse, and the hands of the Queen removed his armor. Doctors came to treat his wounds, which were many, but none caused him great distress.

+

Read more at the Amadis of Gaul website.