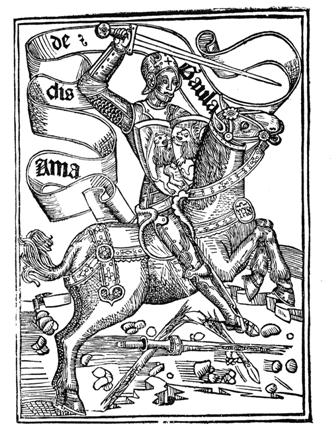

Cover art for the 1508 edition. It set the standard for the chivalric genre: a knight on horseback on the road to adventure.

Amadis of Gaul disappeared after being the favorite of kings and emperors, but not because it was cruelly satirized by Don Quixote de la Mancha. Instead, political attacks and bans eliminated Amadis from respectable bookshelves.

I’ve translated Amadis de Gaula into English. Read it here.

Europe’s first best-selling novel was a Spanish fantasy: Amadís de Gaula (Amadis of Gaul). Written by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, this medieval tale of chivalry was first published in 1496 or soon after. Over the next 90 years, it was reprinted 20 times in Spanish and translated into seven languages. It spawned 44 direct sequels and more than two centuries of spinoffs across western Europe in literature, poetry, opera, theater, and art.

Nobility competed in jousts disguised as knights-errant taken from its pages. Illiterate people thronged to public readings. Everyone in the 16th century knew who Amadis was, just as today everyone knows who Spock is, even if they’ve never seen a Star Trek episode or movie.

And yet you may have never heard of Amadis of Gaul, even though our ideas about knights in shining armor and damsels in distress come from its genre. The book disappeared because it was condemned and sometimes banned, but worst of all, eventually it attracted the wrong kind of fans.

Not an original story

The origins of Amadis of Gaul go back nine hundred years. Tales of King Arthur and Merlin, first compiled by Geoffrey of Monmouth in about 1135, arrived with the Welsh and Breton bards who accompanied Queen Eleanor back to Aquitaine, France. From there, the stories were spread throughout Europe by troubadours like Chrétien de Troyes, who began producing works about the Knights of the Round Table in 1170.

In the Iberian Peninsula in the 1300s, unknown authors fused the virtues of the knights Tristan and Lancelot into Amadis, the greatest knight in the world. He supposedly lived well before King Arthur but in the same medieval fictional setting.

At least two early versions of Amadis existed, but like many other medieval works, all copies (except for the pitiful fragments of four pages) disappeared when the new printing industry devoured old parchments to bind new books. The only surviving version was Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s, which was “corrected and polished” for mass-production from old hand-written manuscripts. The earliest surviving copy of his version (now at the British Library) dates from 1508.

The novel, divided into four books, recounts the life of Amadis. He is born out of wedlock in secret and discovers who his parents are after rescuing his father’s kingdom from invasion. As a knight, he defends the weak from injustice in a wide-ranging series of adventures. He remains faithful in love to Princess Oriana, despite temptation and troubles. Eventually they have a son, also born out of wedlock.

The book is full of sorcery, enchanted weapons, giants, monsters, magical locales, and other “amazing things found outside the natural order,” as Rodríguez de Montalvo described it. The story-telling style is medieval, clearly meant to be read aloud. The complex plot moves fast, and the descriptions of blood-spattered jousts and battles show that the author knew first-hand about fighting.

The Appeal of Amadis

Why did this novel become the first international best-seller? It faced tough competition within Spain and around Europe. I can offer nine reasons:

1. Luck. The printing press had been invented in the mid-1400s, and sooner or later some book was going to hit it big. Latin theological works dominated early production, but printers needed to find more income, so they were looking for popular works in the vernacular.

2. Literacy. The ability to read had spread into the nobility and the new middle class. Both wanted expanded leisure activities.

3. Spanish ascendance. At the time, Spain was the leading European power. People who wanted to study its language and culture looked for Spanish literature.

4. A European hero. The Arthurian cycle had spread across all borders. Amadis came from the fictional kingdom of Gaul and his deeds spanned the continent. Though written in Spanish, it wasn’t a quintessential Spanish story.

5. Renaissance resonance. Since the story originated in medieval times, it provided a nostalgic retreat from the conflicts and terrors of the Renaissance. On the other hand, its theme of heroism played to a sense of individual possibility at a time when real-life horizons were expanding through exploration and renewed scholarship.

6. Kingly authority. During the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, kings consolidated their power at the expense of the nobility, despite energetic resistance. Amadis, always focused on a royal court, reinforced regal power, so kings initially encouraged its propagation.

7. Fun, fun, fun. The literary and religious authorities who condemned it as frivolous entertainment had a point. Love, adventure, intrigue — this book is a page-turner, following a proven medieval structure of several interwoven plotlines.

8. Soaring prose. It was written to be elegantly declaimed. The dialogue seems stilted now, but at the time it set the standard for fashionable speech.

9. Loyal female readers. More on this later.

Triumph and Fall

In all, about 20,000 copies of Amadis of Gaul were printed in Spanish, and at least another 10,000 in other languages — not to mention the dozens of sequels and uncounted spinoffs. This number may seem small, but the population of Europe was only about 100 million, and few were literate.

Also, in those days, one book equaled many readers. Books were actively lent, rented, and read aloud to friends and family (and servants). Readings were held in convents and monasteries and before paying audiences. Don Quixote de La Mancha describes travelers at inns listening to readings of Amadis as a favorite evening entertainment.

Its popularity marked history in amazing ways.

Conquistadors brought it to the New World, “their heads filled with fantastic notions, their courage spurred by noble examples of the great heroes of chivalry,” in the words of historian J.H. Elliott. The novels’ heroes invariably won riches and noble titles, honors coveted by the conquistadors.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortéz’s soldiers, wrote that the first sight of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán “left us astonished, and we said that it seemed like the things and enchantments told in a book about Amadis.” The names Patagonia and California were taken from chivalric novels.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1519-1556) and Isabel of Portugal had it read to them during their siesta by a lady-in-waiting.

When Charles imprisoned King Francis I of France in Madrid in 1525, his sister Margarita read it to the French monarch. Francis liked Amadis so much that he asked one of his artillery officials, the bibliophile Nicolas Herberay des Essarts, to translate the book. Herberay went on to write eight of the 24 French sequels, plagiarizing some Spanish novels and changing the ending of Rodríguez de Montalvo’s version.

Later, portions of the books’ letters, speeches, challenges to enemies, and declarations and lamentations of love, as translated by Herberay, were compiled into the Trésors des Amadis by Robert le Magnier as models of urbanity and eloquence. The handbook enjoyed 20 editions between 1559 and 1606, and was translated into German and English.

Jousts and tourneys, long a favorite festivity of nobles, became re-enactments of the books. A few examples:

In August 1549, María of Hungary prepared a theatric tourney for her nephew, Prince Phillip II, who played the role of Amadis. The event, held in the town of Binche, in the Netherlands, recreated sites and characters from chivalric novels: Dangerous Tower, Fateful Island, the sorcerer Norabroch, a troupe of savage mercenaries, and Phillip/Amadis’s assault on the Tenebrous Castle to liberate imprisoned damsels.

Shortly afterwards, another chivalric novel-inspired tourney in Brussels featured six noblemen disguised as nymphs, wearing tall braided wigs and golden gowns with painted-on breasts.

In 1531, Spain banned all fiction in the New World. Publishers had no intention of losing the market and initially had fiction books smuggled in, but eventually no one paid attention to the ban. When Don Quixote was published in 1605, hundreds of copies were promptly sent to the Americas.

Two years later, in Pausa, Peru, a joust was organized for a festival that included characters such as the Antarctic Knight of Luzisor, the Doubtful Furibundo, the Knight of the Jungle, the Fortunate Knight, the Mighty Brandeleon, the Knight of the Burning Sword, the Gallant of Contumeliano, and the Knight of the Woeful Countenance (Quixote) with his squire Sancho Panza mounted on an ass. The records show there was more poetry and joking around than fighting at the joust.

For the poor who couldn’t afford such gallivanting, shortened versions of chivalric tales were printed in low-cost paperback books and brochures that enjoyed wide distribution for centuries to come.

But the books had critics. This was clear even as far back as the 1300s, when Pero López de Ayala, chancellor to King Enrique III of Castile, called them a waste of time and “proven lies.”

In France in 1588, Michel de Montaigne called them “childish.”

Religious authorities denounced the books because, in the words of Papal legate Antonius Possevinus in 1593, “people turned their back on honest reading, the Sacred Scripture, and works of devotion, letting themselves be dazzled by vain sciences and superstitions like astrology.”

In 1666, Spanish friar Benito Remigio Noydens, in Moral History of the God Momo, a tract against novels of chivalry, wrote:

“They are golden pills that, with a delicious layer of entertainment, flatter the eyes to fill their mouths with bitterness and to poison their souls with venom. I remember having read of a totally dissolute man who, finding himself struck by a young woman and without any hope of conquering her, resolved to get her by trickery and slyness, and, placing in front of her eyes one of these books with an entertaining title, he put in her heart such ideas of love that, following their example, they rotted in her and ruined her honest estate of modesty and her shame.”

Don Quixote Tilts at Amadis

In Spain, chivalric novels suffered occasional censorship in the early 16th century, as did many books, due to some specific problem with their content. Eventually the entire genre came under attack. In 1555, they were banned in convents and monasteries, and in 1560 the Inquisition began to make its suspects confess to reading them.

Meanwhile, the nature of reading had changed. In medieval times, literature had been read out loud, but more and more often people were reading these books silently. Rather than being presented in short segments open to discussion, they were devoured in long afternoons that allowed the reader to identify with the characters, but with no one to draw attention to the moral failures of those figures.

During the reign of King Philip II (1556-1598), new books in the genre couldn’t be printed, and in 1590, two years after the defeat of the Invincible Armada and the malaise that the loss created, existing books could not be republished. Perhaps Phillip was embarrassed by his brief theatrical career in the town of Binche, but the case against the books ran deeper than that.

By the time Miguel de Cervantes published Don Quixote in 1605 (thanks to a lenient censor, Antonio de Herrera), novels of chivalry were seen as a threat to Spain, according to Daniel Eisenberg, former editor of the journal of the Cervantes Society of America. They undermined Spanish cultural centrality because the hero was international. They portrayed open rebellion against authority. They included and even celebrated sex outside of wedlock. “They represented something like the pornography of their time,” Eisenberg says.

Cervantes wrote Don Quixote to attack these novels. In his preface, he claims to have been advised to “keep your eye fixed on the destruction of the ill-founded machinations of the books of chivalry.”

The author succeeded, Eisenberg says: “Starting in 1605, nobody will consider them fashionable or meritorious. Now they are, openly and publicly, second-class reading for people behind the times, for innkeepers, and for old men.”

But as chivalrous novels waned, Eisenberg notes, Don Quixote’s popularity waned, too, until its reappraisal in the 18th century.

Girl Trouble

That’s the official version. But the novels remained popular, if frowned upon, for some time to come. “Don Quixote” took honors in the joust in Pausa, and for many fans, the comic character fell within the norms of the genre, which constantly experimented with its tropes. Twenty new novels of chivalry were written and circulated in Spain during the 17th century — hand-written books, since they couldn’t be printed.

In their early days, the novels had been popular with royalty and nobility, but as time went on, their readership became dominated by women. By the mid-1500s, authors frequently dedicated their books to women. Female characters enjoyed greater importance, even becoming knights. Two women wrote chivalric novels.

Despite condemnation by husbands, fathers, clergy, Cervantes, and the government, women kept reading them. We know this because denunciations and anecdotes continued throughout the 17th century.

Unlike many of those hectors, I don’t believe women read the books for the sex, though the scene in which Amadis and Oriana consummate their love sings with beauty and joy (Chapter XXXV). Amadis of Gaul has another, more important virtue.

Though I couldn’t call the novel feminist, it — and the entire genre — is unusually female-friendly. Even today, some novels barely include women at all, but Amadis teems with ladies and damsels on every page, some in distress and some distressing. Often women and girls serve central roles, like queens, sorceresses, and lovers. Others are messengers, witnesses, assistants, or members of the court. Most don’t have names — so any one of them could be Mary Sue. Any female reader, whatever her ambition, could imagine herself into the novel: a fantasy world of danger, adventure, and fun.

But the fun couldn’t last forever. Fashion, set by men since they controlled the printing presses, had its effect. In the inventories of libraries of noble families, chivalric novels disappeared as if by magic. Amadis of Gaul was not reprinted until the early 19th century, and some Spanish novels of chivalry were not reprinted until the end of the 20th century. Others remain out of print today.

In histories about European literature, Amadis rarely gets mentioned. From the beginning, no one took it seriously. Rodríguez de Montalvo admits in his prologue, “I wished to bring together the writings of light things of little substance … rank fiction rather than chronicles.”

It became popular, beloved, re-enacted, and extended by other authors. It was a best-seller — the first in Europe — historically important, and one of the key works in the development of literature as we know it.

But an exuberant, embarrassing fantasy found no place in the literary canon. Only serious works need apply. The story of the greatest knight who ever lived, full of amazing things found outside the natural order, fell into oblivion.

Works Referenced

Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quijote de La Mancha. Edición del IV Centenario. Madrid: Real Academia Española, 2004.

Eliott, J.H. Imperial Spain, 1469-1716. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1963.

Lucía Megías, José Manuel, ed. Amadis de Gaula 1508, quinientos años de libros de caballerías. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España, SECC, 2008.

Lucía Megías, José Manuel, and Sales Dasí, Emilio José. Libros de caballerías castellanos (siglos XVI-XVII). Madrid: Ediciones del Laberinto, 2008.

Redal, Enric Juan, ed. Literatura en la lengua Castellana, Enciclopedia del Estudiante. Madrid: Santillana Educación, 2005.

Rodríguez de Montalvo, Garci. Amadís de Guala. Edición de Juan Manuel Caucho Blecua, 6th ed. Madrid: Ediciones Catedra Letras Hispánicas, 2008.

Sales Dasí, Emilio Jose. Antología del ciclo de Amadís de Gaula. Alcalá de Henares, Spain: Centro de Estudios Cervantinos, 2006.

Weber, Eugene. A Modern History of Europe. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1971.

This essay was originally published in the Internet Review of Science Fiction in November 2009.