Not every mind is human, which is a challenge for authors. It’s hard enough to write from a different human point of view: we’re a varied species, each one of us with our own experiences and quirks, but at least we can talk to each other. Non-humans … well, they never have long conversations with us, alas.

Yet, if we’re going to write speculative fiction, we can’t let that stop us. For my novel Semiosis, I wanted to write from the point of view of a plant — an alien plant, of course, not an Earthly one. All right, where to start?

Obviously, we know some things about Earth plants, so I began researching them. What is their experience of life? For one thing, they’re under a lot of stress. Growing seasons are short, and weather is uncertain.

Spring ephemerals, such as trilliums and snowdrops, illustrate this anxiety. They grow and flower as early as possible in spring, sometimes right through snow, dangerous though that must be. They catch the sunlight before trees put out leaves and cast shade. They offer nectar to the first bees that wake up after winter, monopolizing their attention. Then these plants go dormant until next spring: that’s the extreme step they must take to get their day in the sun. They leap upward at the first hint of springtime.

Plants compete for sunlight and actively fight over it. A common houseplant called the asparagus fern (Asparagus setaceus) has pretty, lacy leaves – and thorns it can anchor into other plants and climb over them. Its aggression has earned it the status of noxious weed in some parts of Australia. Roses have thorns for the same reason. If they happen to starve other plants by blocking out the sunshine, that’s just survival of the fittest.

Vines climb up trees to get sunshine without the cost of growing a sturdy trunk. Other plants may grow large leaves quickly to cast shadows on their neighbors, or poison the ground to keep out competition.

So, plants lead lives of quiet desperation, in constant combat with a variety of weapons.

The book What a Plant Knows: A Field Guide to the Senses by Daniel Chamovitz documents what his fellow botanists have long known. A plant can see, smell, feel, hear, know where it is, and remember. “Plants are acutely aware of the world around them,” he writes.

Trees, like us humans, have social lives. InThe Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate, German forester Peter Wohlleben describes how trees of the same species in forests create communities that help each other, enjoying much longer, healthier lives than isolated city trees. Trees also make decisions, such as when to drop their leaves, which can be a life-or-death gamble on the coming weather.

Plants are alert to their surroundings, and they can recall the past and plan for the future. They’re gregarious, and being isolated hurts them.

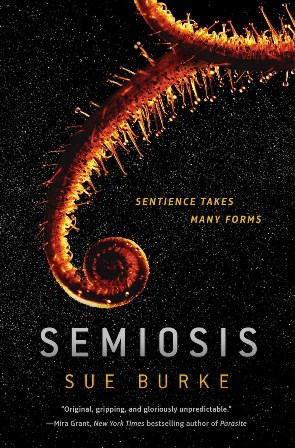

As we would expect from highly aware, social creatures, they relate to other species including animals. They grow flowers to attract pollinators, they grow fruit to encourage animals to spread their seeds, and they enter into symbiotic relationships with animals to further their needs. If nutrients are especially scarce, plants turn carnivorous. (The leaves depicted on the cover of Semiosis are of a sundew. The drops are glue to catch insects.)

Through photosynthesis, plants create their own energy. We can’t know how that feels, although we can observe how sap courses up and down stems and through leaves, and how carefully plants arrange their leaves in a “leaf mosaic” to capture light efficiently. Plants that store food for winter know how much food they have because they stop and shed their leaves when they think they have enough: they have body awareness.

Plants differ from us in one essential way: they have no set body type. Humans have two arms, two legs, and a standard-sized brain. A tree has as many branches and roots as it can support. A single tree can be huge, spreading out from its roots to create its own grove, and some can live for centuries, even millennia.

A possible personality for a plant has begun to emerge: anxious, active, aggressive, alert to its surroundings, impatient, reflective, and forward-looking, physically singular, self-aware, long-lived, manipulative of animals, and painfully lonely if it has no companions of its own species. Add intelligence and we have a point of view:

“Growth cells divide and extend, fill with sap, and mature, thus another leaf opens. Hundreds today, young leaves, tender in the Sun. With the burn of light comes glucose to create starch, cellulose, lipids, proteins, anything I want. Any quantity I need. In joy I grow leaves, branches, culms, stems, shoots, and roots of all types. … Intelligence wastes itself on animals and their trammeled, repetitive lives. They mature, reproduce, and die faster than pines, each animal equivalent to its forebearer, never smarter, never different, always reprising their ancestors, never unique.”